As liquid as ever

Structural power and the future of LNG in Russia's political economy

It is no secret that Russian gas continues to flow to Europe in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG). A recent study conducted by Global Witness found that EU countries had imported 40 per cent more Russian LNG than in the same period in 2021 before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. 22 million cubic meters of LNG were brought to Europe between January and July 2023, which makes the European Union the largest buyer of Russian super-chilled gas, accounting for 52 per cent of exports. Major news outlets in the West, including Reuters and the FT picked up Global Witness’s study, raising the sense of urgency to reverse these upward trends.

It seems obvious that buying more Russian LNG —> increased revenue —> more tax revenue —> padding the Kremlin’s war chest —> military enhancements on the front lines —> tipping the scale of war in Russia’s favor. According to Jonathan Noronha-Gant of Global Witness:

“Buying Russian gas has the same impact as buying Russian oil. Both fund the war in Ukraine, and every euro means more bloodshed. While European countries decry the war, they‘re putting money into Putin’s pockets. These countries should align their actions with their words by banning the trade of Russian LNG that is fueling both the war and the climate crisis.”

This line of reasoning forms the basis of the EU’s multi-sectoral sanctions against Russia: deprive Moscow of export revenues to stymie defense spending. Makes perfect sense, right?

This got me thinking about the way the LNG industry functions in Russia, mainly because many of the mid and downstream activities are privately run. Buying Russian gas does not necessarily have the same impact as buying Russian oil. Several questions popped into my head:

To what extent does the purchase of Russian LNG help the Kremlin and its war efforts? What is the revenue structure for Russian LNG exporters? Where is the money going and how is it being spent? Who is benefitting most from the upward trends in LNG exports?

Some of these questions may be impossible to answer. But they do raise important points surrounding LNG’s impact on Moscow’s overall balance sheet. I decided to take a peak under the hood and see what I could find out about the industry.

Thematically, I found that private actors in the LNG industry have come to enjoy enhanced structural power - and scrutiny - afforded by their stature in Russia’s political economy. Investigating the history of LNG and the private-sovereign relationships therein provided me insight into the future of Russian LNG and its contributions to Moscow’s protracted war effort in Ukraine, as well as the longer-term future of the industry. From my analysis, it is apparent that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused irreversible, structural changes within the LNG industry. It has also brought into focus the rivalry between Russia’s largest state-run and private natural gas producers.

Gas talk

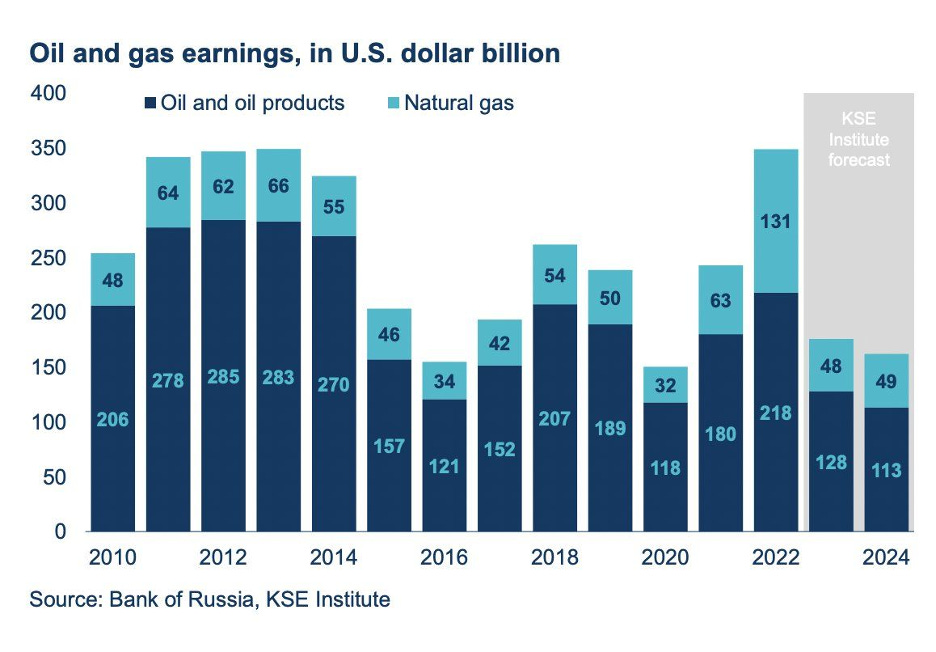

Money from fossil fuels makes up an outsized portion of the Kremlin’s export revenues. In 2022, Russia earned $131 billion selling natural gas. Some project Russia to maintain ‘normal’ revenues in 2023 and 2024, but earnings may be even higher as global prices trend upward this year.

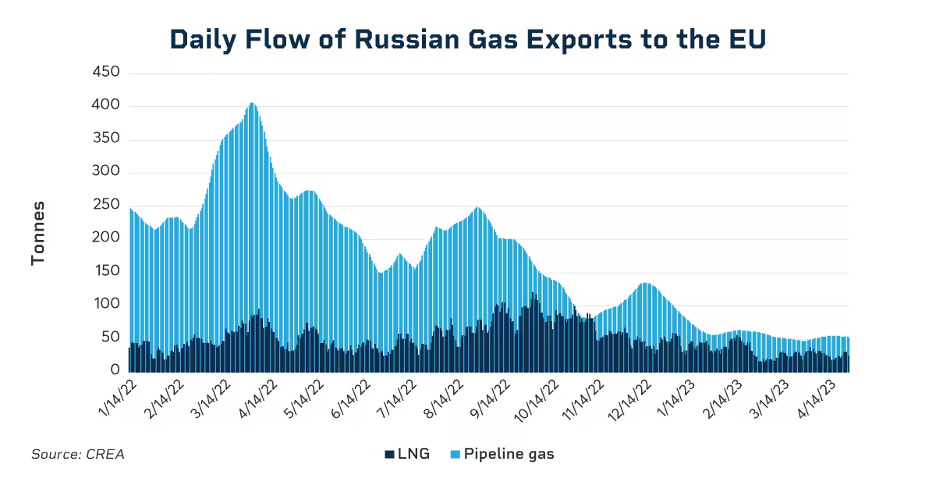

While the EU banned coal, crude oil and products, no sanctions have been imposed on Russian gas transported either via pipeline or overseas. In May of 2022, the European Commission put forth a 210 billion euro plan to help member states become totally independent from Russian fossil fuels, including gas, by 2027. Imports of Russian gas in Europe did drop significantly following EU efforts, thanks in part to a warmer-than-average winter and American producers’ ability to supplant Russian molecules. This was certainly a huge undertaking, as the European Union had imported 155 bcm of Russian gas in 2021, which made up 45 per cent of its total gas supply.

As pipeline imports declined, Russian LNG helped fill the gaps. Spain and Belgium have now become among the largest buyers of Russian LNG, behind only China. Global Witness estimated that the European Union in total will purchase $5.78 billion worth of LNG in 2023, a not-so-insignificant sum when compared to Russia’s overall budget income of $37.4 billion in gas and oil for the first half of 2023. In April, EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson urged member states to stop buying LNG cargoes from Russia.

However, low Russian gas prices in the absence of law and legitimate enforcement have failed to suppress purchasing. Alex Froley of ICIS told the FT that, “long-term buyers in Europe say they will keep taking contracted volumes unless it is banned by politicians.” This is in part because a sudden cutoff of Russian LNG supplies would cause a major shock in European prices. LNG dependence has now become the reincarnation of the pipeline dependence that plagued Europe for decades. And this makes the West vulnerable to Russia’s using LNG as a strategic lever.

The war in Ukraine has accelerated Moscow’s ‘pivot’ to the East - Putin’s strategy of seeking economic growth in Asia in lieu of improving trade relations with Europe. For gas, this was manifested in the Power of Siberia (PoS) and Power of Siberia 2 (PoS2) pipelines connecting East Siberian fields to China. It was also the expansion of LNG export capacity on Sakhalin Island on Russia’s Pacific coast, linking Russia with gas-thirsty Asian consumers such as Japan. By invading Ukraine, Moscow carelessly abandoned most of its European customers and doubled down on its economic wager in Asia.

But the Kremlin has so far fallen short in its pipeline strategy. Russia and China have yet to come to an agreement on the terms of gas deliveries via PoS2 (50 bcm at maximum capacity), while PoS is expected to supply just 22 bcm of gas in 2030. And while experts say that China will not need any additional gas supply until after 2030, quick math makes it seem like rerouting the 155 bcm that once flowed westward to Asian demand centers is highly unlikely in the short to mid-term. Wang Yuanda, also of ICIS, commented in March of this year that, "the original target is for China to import 38 bcm of Russian gas by 2025…Russia is saying this will reach 98 bcm by 2030. That is a very big jump, so it pays to be slightly cautious on that.” This has put all the more focus on Russian LNG as a key driver of Russia’s pivot and a hedge against shortcomings in overland transport to Asia.

A history of LNG in Russia

The history of LNG in Russia is best understood as the downfall of state-run Gazprom and the rise of private producers in the early 2000s, coinciding with Putin’s ascendency to power. The Soviet Union first pursued LNG in the late 1970s with the United States and Japan as the main consumers in mind. But that never happened as politics and regulation largely stymied any progress.

It was only in the 2000s under President Putin that Russia saw the necessity to diversify its export markets beyond its legacy European customers from the Soviet era. It would also improve Moscow’s trade balance and foreign currency reserves, as well as enhance Putin’s geopolitical influence and boost foreign direct investment since LNG projects then required assistance from Western firms replete with the most modern liquefaction technology.

Gazprom, which assumed control of the Soviet gas monopoly during Russia’s privatization revolution and détente with the West, once again saw the United States as a prime export market worth targeting. The company began developing export terminals in the Barents and Baltic seas, as well as on the Yamal Peninsula. Gazprom’s first cargo to the United States arrived in 2005. Its goal in 2011 was to produce up to 15 per cent of the world’s LNG volume and serve Asian markets as part of Moscow’s Eastern pivot. The Russian Federation, aligned with Gazprom’s targets, offered a helping hand by waving taxes on LNG exports for the firm.

But a series of missteps and changing market conditions would challenge Gazprom’s ability to adapt. James Henderson and Vitaly Yermakov of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies delineated reasons why this was the case in a 2019 study on Russia’s LNG emergence. Structurally, Gazprom's leadership struggled to select foreign partners with the technical expertise it needed to develop liquefaction capacity. It also had trouble deciding whether newly developed gas should be devoted to bolstering its LNG business in North America or be sent to Europe through its Nord Stream pipeline to a reliable consumer base.

Other factors out of Gazprom’s control thwarted the gas giant’s LNG ambitions too. The financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 raised the cost of financing one of Gazprom’s pivotal projects in the Barents Sea: the Shtokman field. The project had been stalled by years of deliberations over financing and mixed demand fundamentals in the United States and Europe.

Prospective partners were hesitant to finance the project. They saw the shale revolution unfolding in the United States as the biggest threat to competition (Shtokman was to have a breakeven price of $6/mmbtu, while U.S. Henry Hub prices dropped as low as $1.95/MMBtu in April 2012, for example). The Russian Federation was reluctant to chip in, and the project was postponed indefinitely in 2012 (it was finally scrapped in 2019).

Europe’s energy transition away from fossil fuels and its geopolitical shift away from Russian energy also dampened the prospects for Russian LNG to be the commodity of choice in Western markets. Australia, Qatar, and eventually the United States would go on to provide liquidity and flexibility in the global marketplace.

Perhaps Gazprom’s antiquated business structure and lack of adaptability to new technology didn’t outfit the company well to enter the LNG business. Or maybe it just got unlucky in a difficult market. But Shtokman’s undoing and some other shortcomings at Gazprom LNG projects around Russia led OIES authors Henderson and Yermakov to conclude that, “it is clear that Gazprom’s plans for development of a Russian LNG business have consistently disappointed over the past decade.” This disappointment would eventually lead Putin to - ostensibly - make room for competitors in Russia’s LNG trade in 2013 with the passage of amendments to Russia’s gas export monopoly legislation.

Gazprom maintained a monopoly on all natural gas exports from 2006 until the amendment process in December 2013, wherein private producers were suddenly allowed to export their own natural gas. Some observers questioned whether those new policies actually ‘liberalized’ the market, citing the Kremlin’s gatekeeper role in choosing financeable projects and Putin’s cronies as the main benefactors of decentralization. Nevertheless, these changes allowed new players on the Russian LNG scene to reach FID expeditiously and negotiate deals on preferential terms. The two notable players that emerged were Novatek and Rosneft, which would become Gazprom’s main rivals. These entities would bring in novel approaches that would successfully scale up Russia’s LNG business in places where Gazprom had fallen short.

Novatek and Rosneft began to build up capacity. But Novatek would take the cake. It proved more successful thanks to its ‘no-strings-attached’ development that minimized upstream costs and eschewed geopolitical friction due to its partnerships with the French firm Total and China’s CNPC.

Novatek’s Yamal LNG project was also based strategically on the Arctic’s Northern Sea Route (NSR), which would one day provide reliable and discounted access to Asian markets. The authors of the OIES report attribute Novatek’s success at Yamal LNG to the firm’s decision to assemble an all-star lineup of industry participants: Total for technology, CNPC as a future customer, and China’s Silk Road Fund for financial backing. Efficient project management and R&D also engendered success.

But perhaps Novatek’s greatest achievement was its ability to work around U.S. sanctions that went into effect in 2014. On the contrary, the Gazprom and Rosneft LNG projects suffered when Western partners exited the schemes to avoid sanctions following Russia’s transgressions in Ukraine. For Novatek, Total remained involved all the way until December 2022, when it decided to write off its $3.7 billion stake in the firm.

Yamal LNG also benefited from a unique set of fiscal and economic measures appropriated by the Kremlin. To ramp up production after market liberalization, Moscow offered Novatek tax breaks and exemptions on export duties. Since then, Novatek has leapfrogged its competitors in the Russian LNG industry. It is currently expanding Yamal LNG with its Arctic LNG 2 project set to begin production by the end of this year. Russia would not be in its position as the world’s fourth-largest exporter of LNG without Novatek’s shrewd business strategy over the past decade.

As a result, Novatek has positioned itself as an indelible extension of the Russian state, charged with supplanting Gazprom’s role as chief deliverer of Russian LNG to global markets. The Kremlin has in effect become ‘structurally dependent’ on Novatek for carrying out a vital economic function that the state cannot perform sufficiently.

Today, Novatek has become even more valuable as it recently announced that it developed the capability to liquefy natural gas using domestically manufactured parts without the aid of fleeing Western partners. These are the market conditions we find ourselves in today.

Structural Power and Novatek

The concept of structural power is rooted in the academic field of international political economy spearheaded by scholars Kenneth Waltz and Susan Strange in the 1970s and 80s. These academics were interested in concepts of power and how they influence the modern global system. While there is no single definition for structural power, the general idea is that private firms have come to play a larger role in guiding policy decisions at the sovereign level. Deregulation in many Western economies created room for industries to grow to the point where the corporate strategies of the world’s largest firms - think Meta or Apple - drive social, political and economic change that a national government simply could not with its weakened policy tools. Today, energy firms in particular have become an indispensable part of modern economies because of the foundational goods and services they provide. And sometimes, depending on a nation’s political makeup, a private energy firm can outperform its host government, as we’ve seen with Novatek versus Gazprom.

Francesco Sassi of the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) investigated Novatek through a structural power conceptual framework in a 2022 study titled Structural power in Russia’s gas sector: The Commoditisation of the gas market and the case of Novatek. According to Sassi, Novatek is, “now able to institutionalise its role as the legitimate proponent of the Kremlin’s long-term goals, influencing linked policies and strategies…Novatek is defining its new power relations within the structure, gaining an unprecedented clout compared to any other private player. The same is also synthesised in alternative collective images and transferred to other historical structures, challenging the institution of Gazprom’s predominance in Russia’s gas exports.”

This structural power afforded to Novatek may form an important partnership between Moscow and its largest private exporter. Indeed, Novatek’s independence helped the firm become the LNG success story it is today. But as we’ve seen in this movie before, too much power consolidated outside of Putin’s direct control may eventually lead to expropriation.

Recall the case of Yukos, a Siberian oil and gas conglomerate owned by Mikhail Khodorkovsky. In 2003 Khodorkovsky was the richest man in Russia. His company’s imminent merger/takeover with Sibneft that year would have created the fourth-largest private company in the world. But this business decision, coupled with Khodorkovsky’s activism, challenged Putin’s control and ultimately landed the oil tycoon in prison on trumped-up charges. His sprawling enterprise was subsequently gobbled up by state-owned Rosneft.

This episode demonstrated how Putin can undercut private entities when he gets anxious. Looking around, it is fairly uncommon for a private actor to hold such structural power in the Russian political economy under the current regime. Out of Russia’s top five firms by market capitalization, Lukoil and Novatek are the only non-state entities, accounting for about 22 per cent and 12 per cent of total market capitalization, respectively.

Rivals and friends

The nature of Novatek’s rivalry with Gazprom (and the Kremlin by proxy) has changed over time. It can best be understood as competition, but also by cronyism mixed with the recognition that market liberalization in the gas sector is good for the Russian economy. Novatek’s growth in the early 2000s challenged Gazprom’s ‘single export channel’, which led the Russian Federation to codify the de facto monopoly Gazprom had always enjoyed.

But Gazprom’s persistent shortcomings turned the tides. In 2010, an agreement between Novatek and Gazprom stipulated that gas from Yamal LNG could be sold under a single export channel and Gazprom would skim the top off one per cent of the contract value. But Gazprom, “made absolutely no progress on marketing Novatek gas,” according to Russian gas expert Tatiana Mitrova.

Novatek pushed back. Its lobbyists were instrumental in the 2013 market reforms when the Russian Federation finally acquiesced to the fact that Novatek might just ‘do it better’ than Gazprom.

Political elites provided Novatek’s Yamal LNG project with favorable conditions, including tax breaks and assistance in developing port infrastructure. Powerful actors that were, “generally associated with statism,” came in favor of liberalization. Even Putin, a protagonist of expropriation, cherished Novatek for its results and its development of the Northern Sea Route, a key feature of the Kremlin’s geostrategic foreign policy.

But Gazprom was not so chipper. At the core of the rivalry was the idea that Gazprom's diminished role and Novatek’s preferential treatment had changed Russia’s entire import/export strategy and threatened its energy security. Gazprom was losing out to the new kid on the block as Novatek, basking in tax exemptions, gained entry into European markets that were historically part of Gazprom’s dominion.

So while the relationship between Novatek and Gazprom could be best thought of as competitive, it was at the same time symbiotic. Putin and his oligarchs in charge of running Novatek benefited from the riches of Russia’s hydrocarbon reach.

(Oil)igarchs

At the helm of Novatek are Leonid Mikhelson and Gennady Timchenko, though their statuses with the company have changed over the years. Mikhelson became successful by heading several regional construction trusts during Soviet times. One of his trusts became a private joint-stock company, the Samara People’s Enterprise Nova in 1991, and he the CEO in 1994. Nova, later Novatek, would go on to acquire oil fields in the West Siberian region that would form the cash cow of its business. Mikhelson was once described by Vladimir Milov, a former deputy energy minister, as, “capable of large-scale visionary stuff and getting things done. In the gas industry [he is] a high-level professional… he is number one.”

Mikhelson would bring Timchenko - a self-made billionaire and former energy trader - into the company in 2008. Timchenko purchased a five per cent stake in the firm and a 74.9 per cent share in Yamal LNG through his Luxembourg-domiciled conglomerate called Volga Group. He would later increase his share to 20.77 per cent in 2010, ousting Gazprom as Novatek’s largest investor.

Timchenko was brought into Novatek partly as a hedge against a hostile takeover. Mikhelson saw what had happened to Khodorkovsky in the early 2000s and he became aware of the risks of growing too profitable outside of Putin’s control.

As Novatek looked to raise capital before Timchenko’s entry, a similar situation to Kodorkovsky’s was unfolding for Nikolai Bogachev, a former KGB colonel and owner of the South Tambeyskoye gas field upon which Yamal LNG would be built. A 2022 investigation by The Guardian revealed that Bogachev received the Khodorkovsky treatment as Gazprom took interest in gaining a stronger foothold in the LNG gold rush and leverage over Novatek’s rise. Bogachev’s offices were raided by Kremlin operatives. He was followed and sued. He would eventually be intimidated out of his most precious asset as Timchenko stepped in with financing for the project.

Wary of Bogachev’s undoing, Mikhelson needed a way to insulate himself from an unruly pressure campaign from the Kremlin. Mikhelson brought Timchenko on board to serve as director of Novatek and build a bridge between himself and Putin.

Timchenko and Putin have been close since the 1990s when Putin granted Timchenko an oil export license. Over the years, they’ve benefited from each other’s influence in business and politics. Their relationship has always been intimate: Timchenko helped his buddy raise money to build a 583 million euro superyacht as a Christmas present in 2014. Timchenko’s Labrador retriever is even known to be a descendent of Putin’s own puppy.

With a direct link to Putin’s tightest coterie - and therefore protection against expropriation - Mikhelson and Timchenko would take Novatek to the top, concretizing the structural power that makes Novatek so indispensable. But as history has shown us, continuity in Russia is rare. And so Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would go on to test Novatek’s leadership and resilience in wartime Europe.

Where do we go from here?

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the G7 and allied nations placed countless sanctions on Moscow. Many were aimed at the energy sector, including a price cap on Russian crude that - arguably - held down the price of Russian hydrocarbons. This led to a glut in Russian crude grades, letting India and Asia snatch up Russian barrels at colossal discounts. As a result, Russia’s fossil fuel export revenue fell in the months following the invasion.

And while Novatek wasn’t targeted, the firm was hardly insulated from the sanctions’ negative externalities. The Western response to Russia’s invasion had three significant impacts on Novatek that support my argument. The first is that taxation - once a boon to growth - has become a burden for Novatek. Second, the change in leadership at Novatek coupled with new economic conditions threatens to upend the firm’s status quo and Novatek’s structural relationship with the Kremlin. And third, a reinvigoration of the Novatek/Gazprom rivalry jeopardizes Novatek’s LNG feedstock supply and other cooperative measures.

Tax the rich

How does the Kremlin make up for falling revenue? It increases taxes on non-sanctioned, private producers that can still reach European markets.

Enter our beloved Novatek. It has made a killing during Europe’s ongoing energy crises as the Dutch benchmark TTF hit record highs last summer and Russian LNG became highly competitive. And so, on November 21st, 2022, President Putin signed a law increasing the income tax rate for LNG exports from 20 per cent to 34 per cent in the 2023-2025 period. This amounts to an estimated 200 billion roubles (about $2 billion at a 1 to 0.010 exchange rate) added to the federal budget between 2023 and 2026. Reuters also reported this week that Novatek will soon need to pay an increased mineral extraction tax.

*By the way, to answer my earlier question: “To what extent does the purchase of Russian LNG help the Kremlin and its war efforts?”, according to this estimate Novatek would be paying about 67 billion roubles per year into the federal budget. Bloomberg recently reported that Russia’s defense budget for 2024 is 10.8 trillion roubles. So Novatek’s contribution to the war effort would make up just 0.0062 per cent of this yearly defense budget, enough to build approximately 280 tanks, based on these numbers and a 1 to 0.010 exchange rate*

Novatek pushed back on the tax hikes. Mikhelson asked Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin to grant Novatek’s Yamal LNG a deferral of 2022 profit tax and cut its rate. This alone amounted to 40 billion roubles (about $412.3 million at a 1 to 0.010 exchange rate). But Novatek had no success. It warned that the tax hike would put its 20-million-tons-per-year Arctic 2 LNG project at risk.

Leadership shuffle

Western sanctions on Russian oligarchs targeted Timchenko, forcing him to resign from the board of Novatek. He is no longer a presence in the company. Although Timchenko is still close with Putin, he’s come out publicly saying that he doesn't necessarily support the war in Ukraine.

That leaves the bridge between Mikhelson, now the sole leader of Novatek, and Putin in question. I didn’t find much out there (in English) on Mikhelson’s relationship with Putin since Timchenko’s departure besides the rosy, platitudinal meetings between the two publicized by the Russian State. Mikhelson’s history with Putin is certainly not as extensive as Timchenko’s. And with Timchenko gone, Novatek has effectively become more independent.

Surely Mikhelson has cemented himself as one of Putin’s closest allies. But his preeminence among the Russian elite and Putin’s overreliance on Novatek for hydrocarbon exportation - I argue - make Mikhelson more vulnerable to scrutiny and hostility from the Kremlin.

Rivalry revisited

The frenetic response to Western sanctions from the Russian fossil fuel industry has brought renewed interest to the Novatek/Gazprom rivalry. The real changing of the guard came this year as Novatek officially surpassed Gazprom as Russia’s largest gas supplier to the world.

It is not exactly clear which side Putin supports. Does he protect the old guard, a vestige of Soviet mythology and a national symbol of superiority? Or does he exploit the structural power of Novatek and cash in on the newcomer? Most importantly, does he increase his role in deciding Novatek’s future?

So far I’ve seen only mixed signals.

Putin visited Novatek’s planned Murmansk LNG project in July. In a recent meeting, Mikhelson lobbied for Putin’s backing with Novatek’s planned floating LNG plant in the Kola Bay. No Gazprom representatives were present.

At the same time, a few months after raising the LNG profit tax to 34 per cent, the Russian State Duma passed a law exempting Gazprom from paying this rate.

Gazprom and Novatek have also clashed over determining how to move forward with getting Russian gas reserves to market. Mikhelson and Kirill Polous, Gazprom’s strategy directorate head, have been at odds over their natural gas export philosophies. According to Argus Media, in a swipe at Novatek last year, Polous stated that, “unfortunately, there have been too many calls recently to sell all [Russian] gas overseas,” and that Russia’s LNG ambitions are overoptimist. Mikhelson of course took the other side, telling the St. Petersburg Economic Forum last year that Russia should accelerate its LNG production to, “offset falling pipeline gas exports.”

Novatek, seeing that Gazprom controls the country’s LNG feedstock, has also attempted to make inroads with Gazprom, advocating cooperation to develop Gazprom’s Yamal peninsula fields for export as LNG. But Gazprom has repeatedly rejected Novatek’s bids, opting to team up instead with RusGasDobycha and focus on pipeline exports to Asia.

Conclusion

In this piece, I argued that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has altered the power structures within the natural gas political economy of the Russian state. Changes in the tax code on LNG export profits, firm leadership, and a reinvigoration of the Novatek/Gazprom rivalry have all contributed to these new power structures.

In a time when cooperation is needed between Novatek and Gazprom, the age-old rivalry doesn’t seem to want to break. My belief is that these disagreements will exacerbate so long as revenue from exports stays depressed.

The future of LNG in Russia is promising, don’t get me wrong. But the leadership behind this future, and the decisions made over this future, I argue is not so certain.

As I was writing this piece, Novatek and Mikhelson were finally sanctioned by the United States and the United Kingdom. Now, I don’t know exactly how these sanctions will impact the firm. Novatek seems to be doing just fine with its Chinese backers and proprietary tech. However, these sanctions could put extra pressure on Mikhelson and render him a liability in Putin’s quest for LNG supremacy.

In a perfect world, Europe would be more than capable of living without any Russian hydrocarbons. Civil society groups like Global Witness should continue embarrassing Europe for its overreliance on Russian molecules - nothing else seems to move the needle.

And Europe should keep a close eye on Russia’s LNG industry internally. It may not always be the case that the ‘independent’ LNG it buys from Russia will have - as I have argued - a pretty negligible impact on Russia’s overall defense spending.

I too will keep an eye on this situation. Thanks for reading.

-Zach