Putin's gas mandate (Part 1)

Exploring fiscal policy in the Russian natural gas industry

Russia’s fearful leader

It was no surprise that Vladimir Putin once again won Russia’s ‘neither free nor fair’ presidential election in March. In power since the turn of the century, he will remain at the helm of the Russian Federation for another six years — at least — and will oversee the prolonged war in Ukraine that has kept the Russian economy afloat thanks in part to sustained global oil prices and defense spending. For the time being, most Russians are satisfied with their economic well-being and are confident about the future of their country.

While Putin’s reelection is merely a procedural rubber-stamping of continuity in modern Russian politics, the new mandate does afford the longtime leader a chance to roll out new policy objectives and update existing ones. He did so, ostensibly, in his State of the Nation address in February in which he devoted most of his time to quotidian domestic policy proposals, from doubling the minimum wage by 2030 to new housing targets.

But Putin conditioned these initiatives on the Russian military’s ability to succeed in Ukraine: “Fulfilling all of these plans directly depends on the servicemen who are currently fighting at the front.” He expanded the horizons of a new “holy war” in which Moscow won’t stop in Ukraine but will continue to Russify its near abroad through military and political means. Putin’s fifth term will thus aim to invigorate a whole of society “political vector of pro-war mobilization.”

In effect, more military spending will certainly aggravate an already seared economy. And this comes on top of the $110 - $130 billion in proposed state support for domestic programs.

The Russian economy has remained surprisingly resilient despite Russia’s becoming the world’s most sanctioned nation. Doomsayers that had predicted a financial collapse in the spring of 2022 have been confounded by Russia’s ability to create non-negative GDP growth, maintain low unemployment, and even engender IPO activity on the Moscow Exchange. Even the rouble has found some stability, albeit with some help from the Central Bank.

But the country also faces headwinds that may reverse positive trends: budget increases despite a ballooning deficit, hard-to-predict oil prices, and dwindling foreign currency and gold reserves. The new reality is that the Kremlin’s most reliable macro buffers will limit its policy options. While it has employed several monetary policies to keep the economy alive, it will need to expand on fiscal policy adjustments to address Russia’s budget deficit, which began as soon as the G7 price cap on Russian crude went into effect in early December 2022.

Russia’s feared leader

And so last year Putin did something about it. Tax revenue results from Q1 2024 show how a key change to Russia’s oil and gas tax laws that came into force at the start of this year has already provided the Kremlin with some much-needed cash.

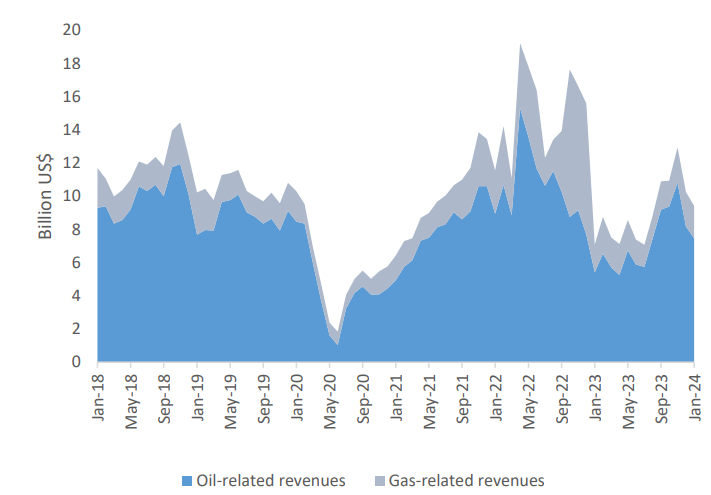

The oil sector brings in the bulk of Moscow’s tax revenue. Natural gas doesn’t generate nearly as much, but its value is geostrategic: in a recent study, Vitaly Yermakov of The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OEIS) wrote that “oil exports matter because of money, gas exports matter because of influence.”

They matter because they are negotiated for longer time horizons than oil. Gas deals signal broader trends in diplomacy and cooperation between Russia and its customers over the next few decades.

It makes sense to explore what state intervention in natural gas production and exportation means for the relationship between producers and the state, and between Russia’s larger economy and society. The natural gas industry has already experienced changes in the tax code since Russia’s invasion. Putin is now eyeing tax hikes on high earners and corporations, which could affect producers and their leadership.

Natural gas has long been an industry held up by the Russian state to accomplish the twin goals of providing energy security and expanding global influence. How much would more fiscal policy complicate these aims?

Analytical direction

Building on previous research for Energist, this commentary investigates how tax hikes — extraction, export, and corporate — would affect the natural gas industry and its place in Russian society. I interviewed Irina Miranova of the European University at St. Petersburg. Irina is a researcher and lecturer in the Energy Politics and Energy Transition in Eurasia (ENERPO) program and is a former Gazprom analyst.

Irina’s recent article in ETH Zurich’s Russian Analytical Digest, titled “Current State of the Russian Gas Market and Export Options” raised questions about Russia’s ability to compensate for export losses to the European market and financial losses on the domestic market. I used this piece in conjunction with other recent publications from Vitaly Yermakov of OEIS and Anne-Sophie Corbeau and Dr. Tatiana Mitrova of Columbia’s Center for Global Energy Policy (CGEP) to anchor my analysis in the background and build on questions raised in the conclusions.

For instance, in his conclusion, Yermakov asks: how sustainable are Russian macroeconomic and fiscal policies in the medium term? And, how long can the government support last and where will the finance for new projects come from?

Similarly, Corbeau and Mitrova raise in their conclusion the painful financial changes vis-à-vis increasing tax burdens that Gazprom faces, in addition to the changing power dynamics between state and private producers.

At the crux of this research is a concept that transcends what typically defines the supply-and-demand nature of the global energy market. There exists a ‘social contract’ between the state and the citizen that raises a ‘pain threshold’ in the population. It is the expectation that the state provides energy security — affordability and reliability — in exchange for the population’s tolerance for the economic pain brought on by Russia’s revanchism abroad.

For some time the state has upheld its end of the bargain through a ‘poker face strategy’: supply gas for cheap while pretending that the external market is flourishing.

But this strategy and this pain threshold are being tested as Moscow comes under more sanctions and has trouble finding new markets for its gas exports.

Setting the economic stage

It’s difficult to report on the health of Russia’s economy as it changes from month to month with the release of monthly government indicators. While March’s economic data were pretty ugly, April’s were quite the opposite. We can pick and choose all we want, but what remains clear is that tax take from oil and gas still matter most in Russia’s budget. Key to understanding the overall picture is that the Kremlin has had to increase taxes to produce the positive economic indicators we see from outside the country.

Doom and gloom.

But February 2024 data from the Russian Finance Ministry showed that the Russian economy is in big trouble. Western sanctions, and recently placed secondary sanctions, have begun to shift the narrative from confounding prosperity to real danger. Steven Tian, a Yale economist, likens Russia’s economy to a house of cards, telling Business Insider that ordinary Russians are, “living regular lives for now, but it's a completely unsustainable strategy, and the fundamental growth drivers underpinning that economy are deteriorating in front of our eyes." To the same source, another economist, Sergei Guriev of the London Business School, compares today’s Russian economy to that of the late Soviet Union.

During that time, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev raised investment and defense expenditures despite falling tax revenue. The CIA contended that Soviet officials grossly underreported the USSR’s deficit from 1985-1988 and that in fact, it had more than tripled during that period from 25 billion roubles to over 80 billion. In 1989, the Soviet budget was projected to reach $162 billion by 1990.

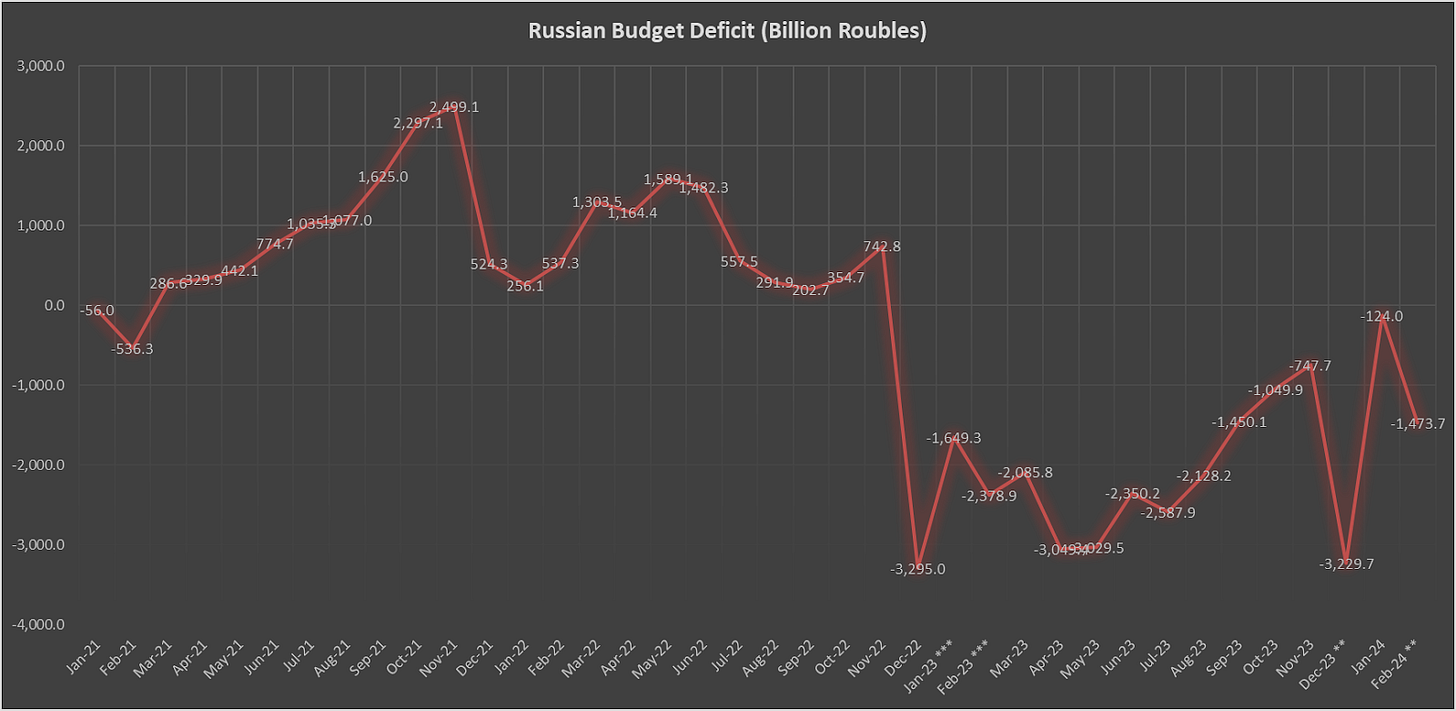

Indicators over the last year have shown that Moscow’s spending has once again gotten out of hand. The budget slipped into deficit territory in late 2022 as revenues from oil and gas fell due to the G7 price cap and lower global prices:

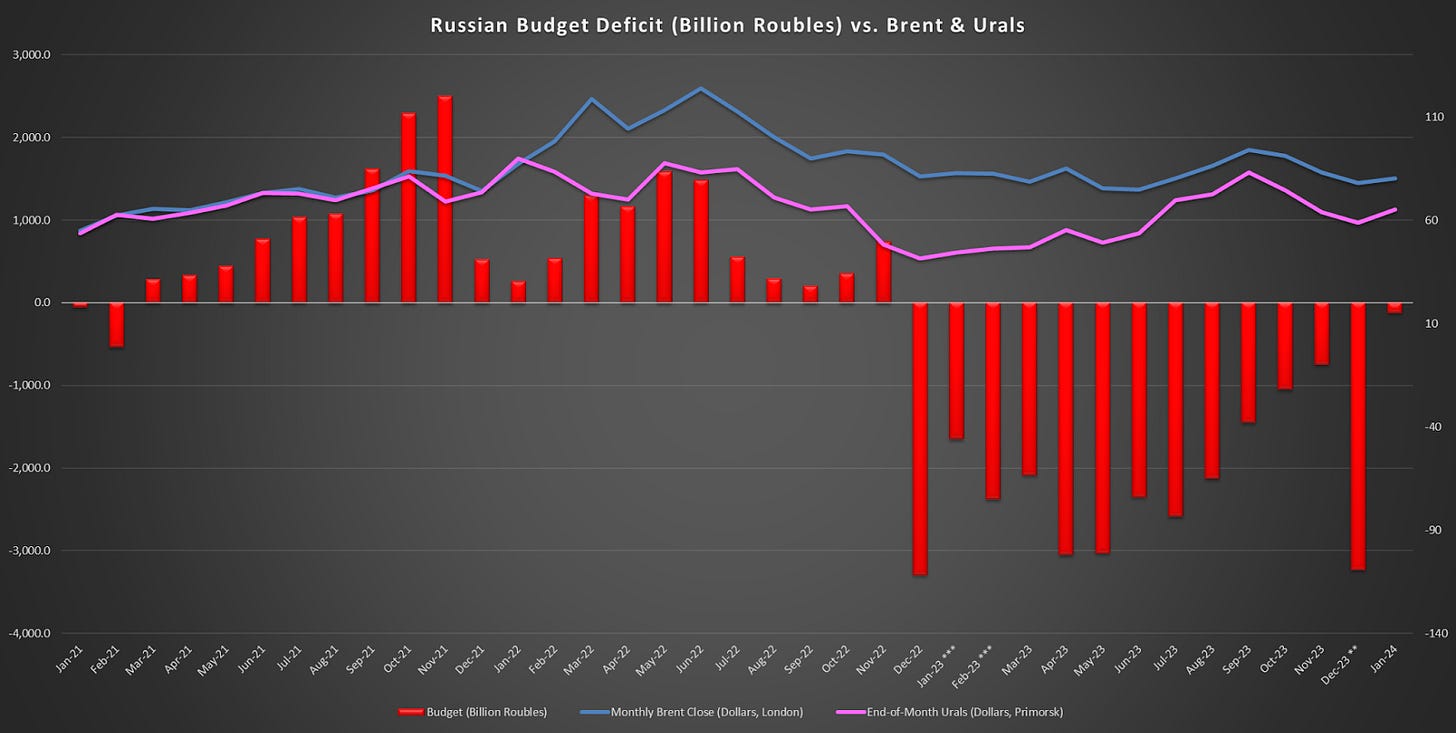

When compared to the global price of oil and Russia’s flagship blend, it’s easy to see just how much oil prices have impacted the Kremlin’s budget:

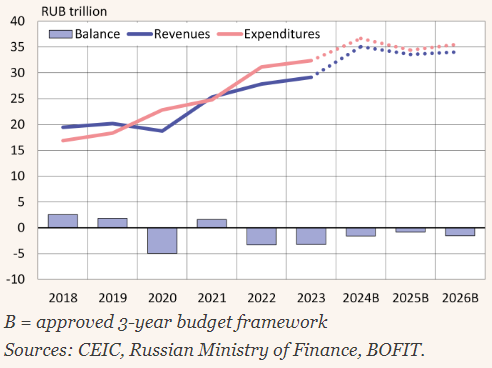

The deficit was 300 billion roubles larger than anticipated in 2023, and the government shows no sign of slowing down. It plans on running a deficit for the next two years at least — 28 percent of the budget will go to defense, while another 9 will go to ‘national security’:

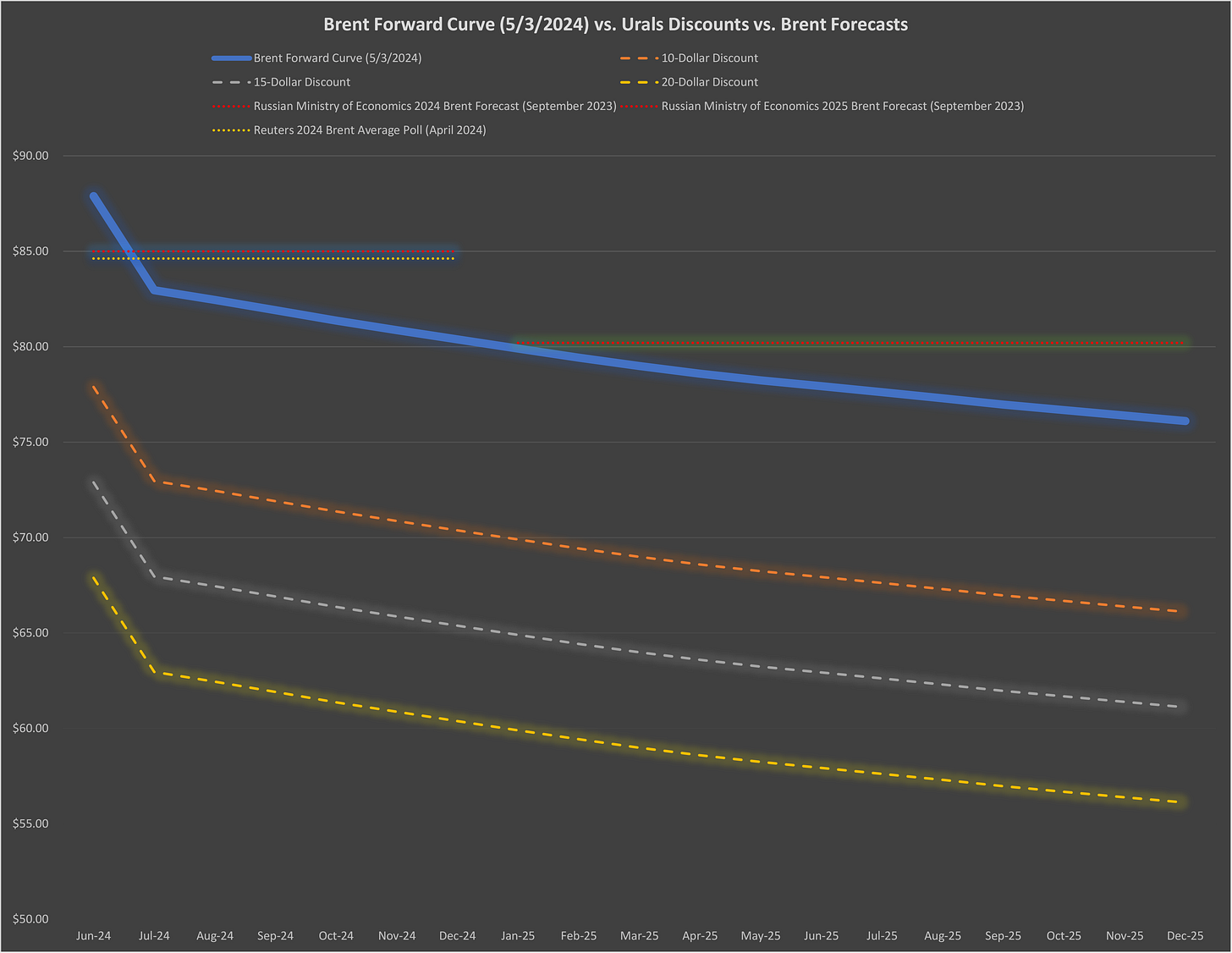

Russia’s budget is highly dependent on revenues from oil and gas — its Ministry of Finance uses a price-of-oil base case to guide fiscal policy. For 2024, the Russian budget follows an Urals $70-per-barrel assumption. Considering the forward curve (as of 5/3/2024) and 2024 average forecasts for Brent, and hypothetical Urals discounts (the real one has recently widened), it’s clear that Russia’s typically conservative budgeters were overambitious when assuming the export price for oil. If the Brent forward curve stays backward through the year, spot prices would exceed forecasts:

So much depends on the price of oil this year to meet the Kremlin’s expectations. Though revenues from oil and gas have largely remained robust, they are not enough to keep up with Moscow’s spending. Researchers at the Kyiv School for Economics Institute recently projected that oil and gas exports will decline over the next two years, reaching $179 billion in 2025, down from $225 billion in 2023.

Where to go for extra cash? Look to Moscow’s foreign currency and precious reserves in its National Wealth Fund (NWF), which the Federation has kept robust amid its risky adventures abroad.

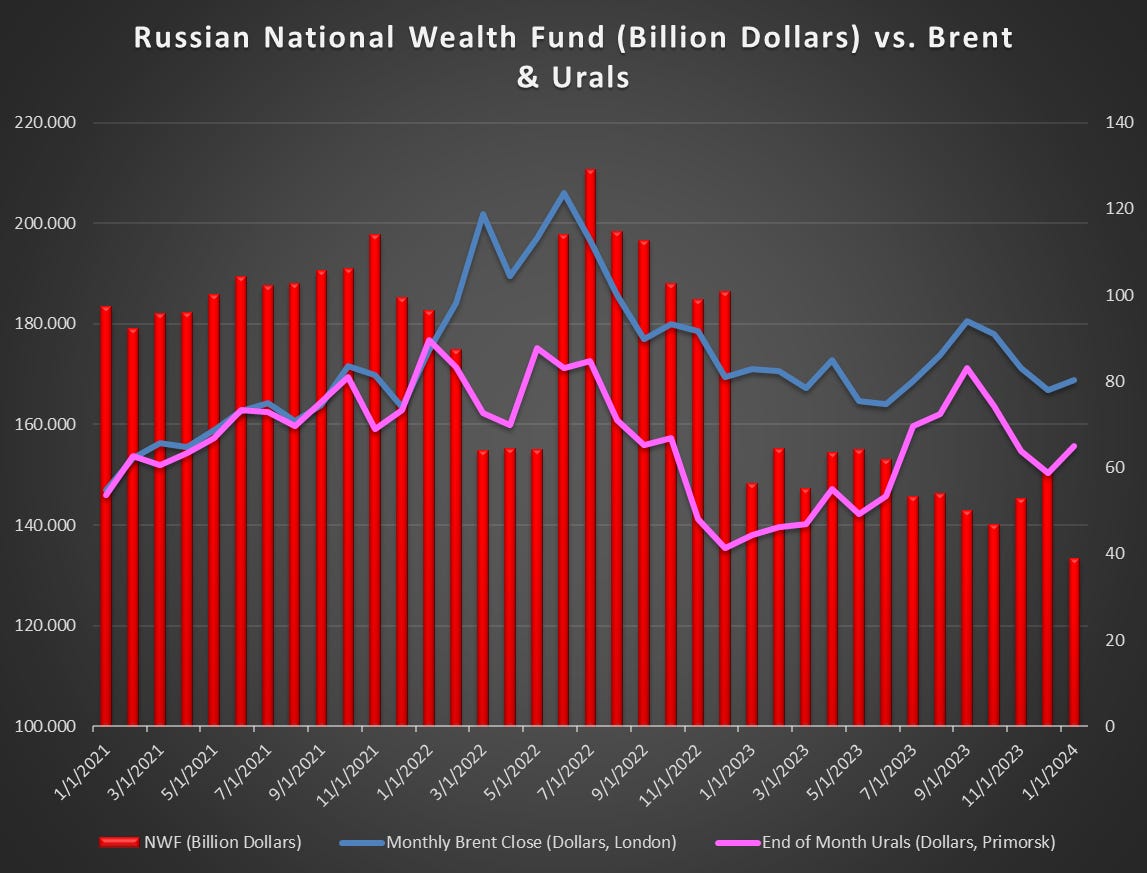

But the government has been quickly burning through these NWF reserves as it hemorrhages cash in Ukraine and ramps up its military-industrial base. In Roubles, Moscow’s liquid holdings slumped from 8.9 trillion before the war to 5 trillion at the end of 2023. The NWF, which is made up of roubles, foreign currencies, and gold among other assets, has been falling since the Brent/Urals gap started to widen in December 2022. But it hasn’t been able to catch up to the bump in Urals early this year — NWF levels typically track Urals prices, but since July 2023 the two data points have diverged. As of January 2024, the NWF was at its lowest point since April 2020:

If Urals drops dramatically, let’s say, back to its nadir in January 2023, Moscow will exhaust its reserves at the start of 2025, according to the aforementioned economist Yevgeny Nadorshin: "Simply put, Russia no longer has insurance against low oil prices.” Further, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov puts this price at $48 per barrel.

But also boom.

March’s data seems to reverse those downward trends. The Kremlin’s budget reentered surplus territory at 867 billion roubles. Overall budget revenues for Q1 2024 were up 53.5% compared to the same quarter last year.

Two main factors suggest why what we see as doom and gloom now looks more like boom. The first is higher oil prices for this period — oil & gas revenues for Q1 2024 were 79% higher than Q1 2023. The second is the key change in Russia’s tax oil and gas tax code, mentioned in the introduction.

A recent economic update from The Bell admits that Russia’s budget deficit isn’t a very good indicator of financial stability. Rather, where the money comes from is what counts. Let’s get into it.

Price-dependent revenues.

Time will tell where prices go this year and how much revenue Russia raises. Jitters in the Middle East may keep them elevated. While oil prices counterintuitively slipped after Iran attacked Israel, sentiment among oil options traders seems more bullish. But even after Israel retaliated some days later, Brent couldn’t break $90. It is down to almost $80 per barrel as of the time of writing. So it seems that OPEC has a good grip on the market, where fundamentals reign supreme and geopolitics matter less. Production in the United States has shattered records, helping to drive prices down as well.

On the demand side, appetite for Russian energy may decrease: a refinery operator in India — a loyal customer — recently said it would stop buying oil from sanctioned Sovcomflot tankers. The shadow fleet transporting Russian barrels to market might have also seen its peak. Yet, customers like China continue to gorge on Russian oil like there is no tomorrow.

With this uncertainty, Russia’s ability to contain the budget requires advancing fiscal adjustments already in place. More taxes, or different tax strategies, have implications for the relationships between oil and gas producers and Russian society writ large. Yermakov warns:

“If solutions are not found, the risks of very negative developments on the export revenue side will become apparent…ultimately reducing Russia’s macro-economic stability and shattering the historic social contract around gas supply to the domestic market.”

Taxes on the oil and gas industry

The Kremlin’s tax policy and the fossil fuel industry in Russia have an important relationship that changes the way we view the Russian economy.

While Q1 2024 results reflect higher global oil prices, they don’t necessarily reflect the actual value of what Russian producers pull out of the ground relative to the dollar value of global energy. This is because of, among other fiscal levers, a new revision for calculating the mineral extraction tax (MRET) that went into effect at the beginning of 2024. It came as a way to make up for windfall caused by rocketing oil and gas prices over the past two years and is the latest development in a 20-or-so year of tradition in raising money from exporting fossil fuels. In his detailed report, Yermakov lays out the history of taxation in the Russian oil and gas sectors which I will summarize in brief:

As the ‘twin workhorses of the Russian economy’, oil and gas have generated immense revenues for the Russian state since the country transformed into a well-endowed market economy through the 2000s. The Mineral Resource Extraction Tax (MRET) and the export duty tax are the two main channels through which Russian hydrocarbons are taxed, with a sliding scale formula that reacts to global prices. This was meant to shield producers from volatility and ensure their minimum operating margins. Indeed, this led the sectors to survive the price crashes of 2009, 2015, and 2020.

The MRET is a one-size-fits-all tax that tends to favor state projects while creating high up-front costs for new developments. As a result, MRET exemptions started to creep in through the 2010s. Almost 60 percent of oil fields in Russia received exemptions from MRET. By 2035, the Russian Ministry of Finance feared that 90 percent would require exemptions.

This led to Russia’s adoption of the additional profits tax (APT) in 2019 and full implementation in 2021. APT was set at 50 percent and featured deductions for production and transportation costs. Yermakov points out that APT’s main advantage was producers’ ability to expense capital losses. The tax raised $13.7 billion in 2021 and accounted for 11 percent of oil-and-gas-sector taxes. In 2022 it was $24.7 billion and 15 percent. By 2023 APT dipped back down to $15.1, but still contributed 15 percent to federal taxes from oil and gas.

APT became an important fiscal instrument to address the needs of producers and provide an additional layer of oil production resilience. In essence, the flexible taxes work as a stabilizer for the Russian government. It can take more when prices are high and provide support when prices are low.

Over time, the tax burden has shifted to the MRET at the upstream production on volumes instead of global price — taxing at the well instead of when exporting. This ensures that the Kremlin covers barrels and molecules before they are exported at varying prices. Invariably, for example, this led the Kremlin to guard against certain fuel oil exporters’ taking advantage of minimal export taxes by introducing a negative excise tax in 2019. These measures help keep the domestic market supplied at predictable prices.

My takeaway is that Russia’s taxation over its most strategic sector is a seemingly impossible three-pronged approach: safeguard against external price shocks, subsidize domestic markets, and provide flexibility for exporters to reach desired markets. I say seemingly impossible because this model operates under a few assumptions that are changing:

Not price shocks, but price depressions from Urals/pipeline gas discounts and;

Unpredictable demand from unpredictable customers

How sustainable is this approach when the underlying assumptions change and when fiscal policy must escalate?

To be continued…

In Part 2 we will look deeper at this question and turn away from crude and toward natural gas, our fuel source of choice. The Russian Federation treats natural gas differently from crude oil. As such, taxes in this category have unique consequences. Part 2 will also account for short-term changes in economic indicators that may refute or support the existing analysis. Please consider subscribing to Energist to receive Part 2 directly to your inbox.

-Zach