Powerless in Siberia

Why President Vladimir Putin remains so "upbeat" about Power of Siberia 2

Last February, Russia and China announced that they had formed a ‘no limits’ strategic partnership to stymie Western interests around the globe. Since then, in many ways, this partnership has had some substantial limitations. One is in energy, specifically in Russia’s unfinished overland pipeline to China called Power of Siberia 2 (PoS2). The PoS2 partnership has come to resemble something more akin to unrequited love or false hope: Moscow believes that Beijing wants more of its natural gas but Beijing doesn’t feel quite the same.

Russian President Putin has left meeting after meeting with Chinese President Xi convinced that he and his Chinese counterpart are just one step away from finalizing a deal. But Xi has shown to be reliably noncommittal, having never pledged full support for the project.

Why then, does Putin remain so “upbeat” on PoS2? Surely he’s aware of the poor economic prospects of the project. And as an experienced statesman, surely he’s taken a hint from Xi’s bitter lack of enthusiasm. From what I found, the answer has to do more with politics and optics than economics.

First Love

PoS2, also known as Altai, is a proposed natural gas pipeline owned and operated by Gazprom that links Russia’s gas-rich Yamal peninsula through Mongolia to China. As the name suggests, this 50 billion cubic meter per year (Bcm/y) route will add to Russia’s overland exports to China through the original Power of Siberia (PoS), which connects gas fields in east Siberia to China’s northwestern region.

For the past decade, Putin has steered his economy away from reliance on European customers to develop new markets in the East. This “Pivot to the East” was a feature of Putin’s reelection platform in 2012, when he wrote in a series of ‘program statements’ that China’s growth, “carries colossal potential for business cooperation - a chance to catch the Chinese wind in the sails of our economy.” The Russian premier hopes to deliver 98 Bcm/y in addition to 100 million tons (mmt) of liquefied natural gas (LNG) by 2030. Indeed, Beijing needs more natural gas as part of its domestic energy strategy to replace coal-fired power generation with cleaner alternatives.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have expedited this shift. Western sanctions on Russia’s energy sector coupled with Europe’s (albeit slow) move away from Russian hydrocarbons have increased the imperative for Moscow to solidify its Asian customers. That’s why in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Presidents Putin and Xi signed a $400, 38 Bcm/y agreement for gas deliveries through PoS. This deal was Moscow’s escape pod from its self-destructing invasion of Crimea that soured many European capitals’ appetite for Russian molecules.

Gas began flowing at the end of 2019. Celebrated as a ‘landmark project of bilateral energy cooperation,’ Putin remarked that, “this step takes Russo-Chinese strategic cooperation in energy to a qualitative new level and brings [Russia] closer to (fulfilling) the task, set together with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, of taking bilateral trade to $200 billion by 2024.”

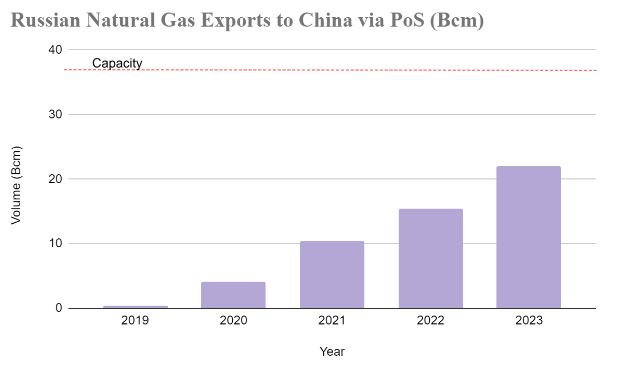

Price over volume

In part because of the war in Ukraine, trade between Russia and China is on pace to reach its $200 billion goal this year ahead of schedule. And natural gas exports have certainly added to this growth. Gas supply through PoS over the past four years is on pace to reach its full 38 Bcm/y capacity by 2025: in 2020 4.1 Bcm flowed through PoS, in 2021 Gazprom supplied 10.39 Bcm through PoS, 2022 saw a 49 per cent increase year-over-year with 15.5 Bcm transported, in 2023 PoS is expected to supply around 22 Bcm.

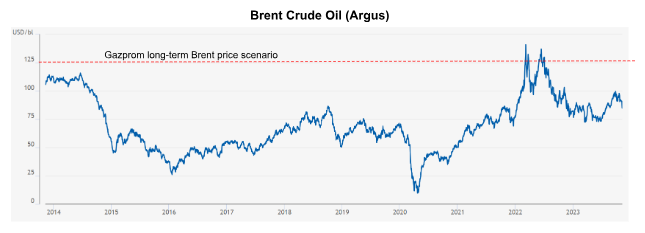

While these volumes are robust, the actual value of the gas, and thus the economic impact, is more uncertain. Gazprom never disclosed its pricing formula negotiated with China for PoS in 2014. But Sergey Vakulenko of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace posited that Gazprom negotiators most likely used a pricing formula indexed to Brent crude with a long-term scenario of approximately $125 per barrel, a not-so-bullish outlook when the PoS deal was inked in 2014, but not so lucrative retrospectively. Brent priced consistently under Gazprom’s long-term oil scenario since 2014, popping over only ephemerally during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other researchers have speculated that Russia loses money on PoS when oil is lower than $60 to $70 per barrel, as was the case for several years.

Vakulenko calculated that this formula would yield an estimated sale price of $350 to $400 per 1,000 cubic meters for natural gas transported through PoS over thirty years. However, he found that during 2020 and 2021, China paid Gazprom much less than its long-term Brent price scenario, and much less than China’s historic suppliers, namely Myanmar, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. In 2020, Chinese customs data showed Russian pipeline gas averaging $4.15/MMBtu compared to $9.08/MMBtu piped in from Myanmar.

In sum, China has gotten a pretty good deal over the past decade on gas from PoS, while Gazprom executives wish they had been tougher at the negotiating table in the first place. These historical lessons should inform deliberations over PoS2 as Putin tries to convince Xi that China needs more Russian gas.

Rebound

Turning to the Chinese market was Putin’s logical next play after largely severing pipeline gas relations with Europe, a 150 Bcm/y market once worth $400 million per day. With Europe out of the equation, it is estimated that Russia has about 100 Bcm of gas with nowhere to go. Gazprom hopes that the 3,550 km PoS2 can take 50 Bcm/y of that gas to China by 2030, rerouting formerly Western-bound molecules from the Yamal peninsula to the high-demand centers of China.

But the second project has come up against a number of challenges that make President Xi wary of committing to any long-term deal. Primarily, many question whether Beijing even needs more Russian gas.

On the supply side, the original PoS still has 16 Bcm of spare capacity to grow with below-market-priced gas between now and 2030. China has prioritized sourcing gas from Central Asia instead of Russia. PoS2 will have to compete with Gazprom’s 10 Bcm/y pipeline from Sakhalin in Russia’s Far East. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) will also factor in - Beijing has locked in long-term LNG contracts with Qatar, the United States, and the Russian independent competitor Novatek. China too has begun to tap into its domestic ultra-deep natural reserves. Its upstream investments reached a record of $51.2 billion in 2022, an increase of 19 per cent year on year - it now produces enough gas to fulfill 59 per cent of its domestic needs.

As for demand China’s need for natural gas is expected to peak in 2040. Its gas relations with Russia will likely end in 2060, if not sooner, rendering PoS2 obsolete. China will also ramp up its renewable energy usage. Some researchers point to China’s energy transition as a key factor that will ultimately dampen the demand for natural gas in the mid to long-term.

The financials aren’t so convincing either. Construction of the pipeline may prove to be higher than expected considering Russia’s ballooning interest rates and tight labor market.

The return on investment too is anything but rosy. Building on his pricing work for PoS, Vakulenko proposed that Gazprom will have no choice but to use a similar oil-pegged formula to price PoS2 if a deal ever materializes. This formula yields about the same netback per 1000 cubic meters for PoS2 as PoS, and much less than what it used to bring in from Europe. Gazprom can add 50 Bcm/y ~ at best ~ to its total export volume through PoS2. But this will fail to make up for the preponderance of 150 Bcm/y of gas Moscow exported to the European market before the invasion in 2022.

At those low prices, there is no way of knowing whether PoS2 will be worthwhile or a total flop. Most experts would bet good money on the latter. Yet the men with the most to lose have doubled down with conviction that PoS2 will be the savior of Gazprom as its huge income streams that support the Kremlin’s coffers wane.

Many analysts have suggested that Xi enjoys more bargaining power the longer he waits to commit to volumes. Besides the Yamal gas still flowing to Europe in the form of LNG, Russian Arctic gas has no other market outside of China, according to Vakulenko in a conversation with The Bell, a Russian independent news outlet. He adds that it’s in China’s interest to wait for new liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) from Qatar and the United States to come online before negotiating a price for PoS2. Doing so would likely yield an even sweeter deal for Beijing in this buyer’s market environment.

China’s energy security strategy has long focused on diversifying supply, and natural gas is no exception. Xi would be averse to relying solely on Russia for any one commodity and become susceptible to the excessive reliance Europe experienced for decades. Uncertainty surrounding the war in Ukraine also affords China leverage in the negotiations.

Dating dissonance

Putin and Xi have met multiple times over the course of the year. Putin’s main goal in a March 2022 bilateral was to convince Xi to get on board with PoS2. However, a joint statement that emerged from the meeting mentioned no agreement over the project. Instead, the leaders embraced vague platitudes such as, “strengthening the comprehensive partnership in the energy sector,” and making, “efforts to advance work on studying and agreeing.”

But Putin told a different story to a different audience. The Russian leader, who walked away from the summit claiming he had struck the ‘deal of the century,’ boasted that, “practically all the parameters of that agreement [PoS2] have been finalized.” True? Technically. Misleading? Definitely. His Deputy Prime Minister Aleksandr Novak also jumped the gun in a fait accompli: “The project has support. Companies have been instructed to work out the details of the project and sign it as soon as possible.”

At their next meeting last month, Presidents Xi and Putin spoke on the sideline of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRFIC) in Beijing to revisit their no-limits partnership. Yet again, the leaders failed to reach a deal - the pricing formula, supply volumes, and mandatory purchase levels (take-or-pay) remained the major impediments. How awkward, though, because according to Argus Media, in a different sideline chat at the very same forum, Putin told Mongolian president Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh that, “everyone [at the forum] agrees with this project, all parties want to participate, want it to work, it’s a matter of implementation. I think we will move at a good pace.”

Childish it seems for Putin to embellish reality to a peer with whom Gazprom needs to cooperate for the project. The more Xi remains tepid on the project, kicking the can down the road meeting after meeting, the more desperate Putin and his gas oligarchs become. Revealingly, the headlines write a melodrama of desperation starring Russia as the forlorn clinger:

Rejection has led the Kremlin and Gazprom to unleash a whirlwind of self-affirmation to convince themselves and relevant parties to stick with the project. Gazprom has made unsubstantiated and outright false claims about its export future to China: its pipeline supplies to China will soon match the volumes once sent to Western Europe, it will become China’s top natural gas supplier when the PoS system reaches full capacity and its PoS2 negotiations had become ‘more active’ even before the October reunion. These assertions are often directed at the Russian domestic audience and air on widely viewed channels such as Rossiya-1 TV and Izvestia.

Upbeat, but not on the balance sheet

I spoke with Joe Webster about this question. Webster is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center and editor of the China-Russia Report. Like other analysts, he suggested that the reason that Putin keeps pushing is that has no better options - Europe is lost and China is the only future. Putin matches Xi’s tepidness and patience with his own persistent zeal televised to an indoctrinated audience. Webster told me that it is, “politically more convenient for [Putin] to draw out the process and hope for a deal from China or, perhaps even less likely, a shift in European political economy.” The economic downside of the project could indeed provide political upside as long as Putin hammers this idea that Gazprom has a bright future in China.

For Putin, Gazprom is more than just an indispensable revenue generator and a state-run entity tasked with bringing energy to the global market. I’ve explored this idea in a previous article titled As liquid as ever: Structural power and the future of LNG in Russia's political economy. I argued that Gazprom transcends any rational economic thinking in the psyche of the Kremlin. It is a vestige of Soviet mythology, a symbol of national unity and proof that the historically paranoid Russian state can maintain control over its vast territorial expanse. The aging company faces increased competition from outside rising LNG superpowers within Russia too. Independent producers such as Novatek have amassed the winning export strategies, technology and political backing to outperform Gazprom in a world where access to the European market is disappearing in the rearview mirror. In August, Novatek surpassed Gazprom to become Europe’s largest natural gas supplier. And just this week, Gazpromneft, a Gazprom subsidiary that produces oil, became more valuable than its much larger parent company, according to a Eurasia Energy report from Argus Media.

The general theme is that Gazprom is declining while Novatek and other independent producers are rising in prominence. Putin is ambivalent about accepting this reality, recognizing that he benefits from having a wider global LNG footprint while ceding some authority in how Russia’s hydrocarbons are used to accomplish geostrategic objectives.

Gazprom thus serves as a proxy for Putin’s control over state institutions. Besides drawing out the process for political convenience, Putin seeks to remind the world that Gazprom is still relevant, and therefore Russia is still relevant. He often brings an entourage of journalists and media personnel to his meetings with Xi, directing them to portray him to the Russian Federation as a ‘world-class leader’ who commands the world’s attention and whose meetings with Xi are a symbolic ‘triumph over the West.’

No one understands better than Putin that optics are everything. But his big bet on PoS2 will probably come back to bite him when the economic realities materialize after many more months, even years, of clinging to a noncommital partner playing the field.

Putin has sabotaged Gazprom at every turn over the past 20 years because when it was well-run it was a threat to its power (given that the company literally keeps Russians alive). It used to a company run by engineers (and easily underestimated from the outside) and politics played out once the results were obtained (in the words of an old Gazprom hand "first we generate the money (after meeting our public obligations) then we steal it"). But the price increases from 2000 have left so much income that it no longer became necessary for Gazprom to be well run ("there was so much money to steal that we ould not steal it all").

Destroying the reliability of Gazprom as an exporter is the final nail in the coffin, and China is certainly not a viable alternative for a company built for the past 50 years around its Western-directed backbones.

Interesting article and great title!

The first part gave me the impression that Xi was “playing” Putin but the comment from Joe Webster gives the impression that Putin is no fool and is actually playing his domestic audience.

> In August, Novatek surpassed Novatek to become Europe’s largest natural gas supplier

I assume this should read “Novatek surpassed Gazprom”?